Earth Law Center Blog

To Kill or Not to Kill? The Controversial Plan to Kill Half a Million Barred Owls

In November 2023, the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) published a proposal to kill roughly half a million barred owls to protect a species that barred owls outcompete—the endangered spotted owl. Since then, the USFWS finalized its strategy to manage the barred owls and plans to begin implementation as soon as spring of 2025. The plan to kill barred owls has sparked controversy, with proponents and opponents both advocating fiercely for their positions.

In this blog post, we investigate: What has led to the present moral crisis at hand? Why does the USFWS argue that the killing of barred owls is necessary and justified? And what is an Earth law perspective on this issue?

Earth Law Center at COP16: An Interview with Grant Wilson

The following interview was conducted by Earth Law Center (ELC) intern San Kwon with ELC Executive Director Grant Wilson, who attended the 2024 UN Biodiversity Conference (COP16) in Cali, Colombia, from October 21 to November 1, 2024.

COP16 was the sixteenth Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, which was drafted in 1992 and is currently guided by the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, adopted in 2022.

Vanuatu Leads Recent Initiatives in the International Push for Environmental Justice

Vanuatu, a Small Island Developing State (SIDS) in the South Pacific Ocean, has recently spearheaded two major developments on the international level concerning the Rights of Nature and climate justice.

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) passed a resolution requesting an advisory opinion by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to clarify the legal obligations of States concerning climate change. In addition, Vanuatu, along with Fiji and Samoa, have asked the International Criminal Court (ICC) to consider ecocide an international crime.

This blog post details these important developments and their significance for the international community.

Inherent Relationships Jurisprudence: An Indigenous Environmental Network and Earth Law Center Collaboration

Indigenous Environmental Network (IEN) and Earth Law Center (ELC), two organizations deeply committed to protecting the planet and upholding the rights and responsibilities of Indigenous Peoples, are collaboratively developing a long-term project on Inherent Relationships Jurisprudence. The collaboration seeks to explore the benefits, opportunities, and challenges of Traditional Indigenous Knowledge-based legal frameworks and the Rights of Mother Earth (or “Rights of Nature”), with a focus on legal applications by Indigenous Peoples and Nations.

Rooted in Nature: Earth Law Center Summer Internships in Durango, Colorado

While urban environmentalism is a core tenet of the ecological movement, my metropolitan notion of land protection was based on pictures and imaginings of distant imperiled landscapes. Earth Law Center is headquartered in Durango, Colorado, a town nestled under the shadow of the La Plata Mountains, mere minutes from the desert, with the Animas River flowing through the heart of downtown. Just days after arriving in Durango, I find myself in conversation for the first time with my long-time pen pal, Nature.

Food Sovereignty, Indigenous Practices, and Ecocentric Law

As the world begins to reckon with the unsustainability of industrial agriculture, we are seeing growing interest in the possibility that the ecocentric farming breakthroughs the world needs are here now in the form of traditional Indigenous agricultural methods and their modern adaptations. Indeed, Indigenous communities have a more ecocentric approach to food sovereignty and agriculture than the dominant Western approach, which focuses on production volume rather than the long-term health of the land.

Could “Harmony with Nature” Overtake “Sustainable Development” as the UN’s Primary Environmental Ideal?

This post examines the history of the concepts “Sustainable Development” and “Harmony with Nature” at the United Nations, and argues that it is time to embrace the latter as a non-anthropocentric environmental ideal.

ELC’s Latin America Program Advances Rights of Nature Strategic Litigation via Amicus Curiae Briefs

Earth Law Center’s Latin America team drafts amicus curiae briefs on the Rights of Nature as a tool to cross-pollinate Latin American courts with the ecocentric perspectives of comparative law and supranational courts, an important step toward legal recognition of Nature’s intrinsic value.

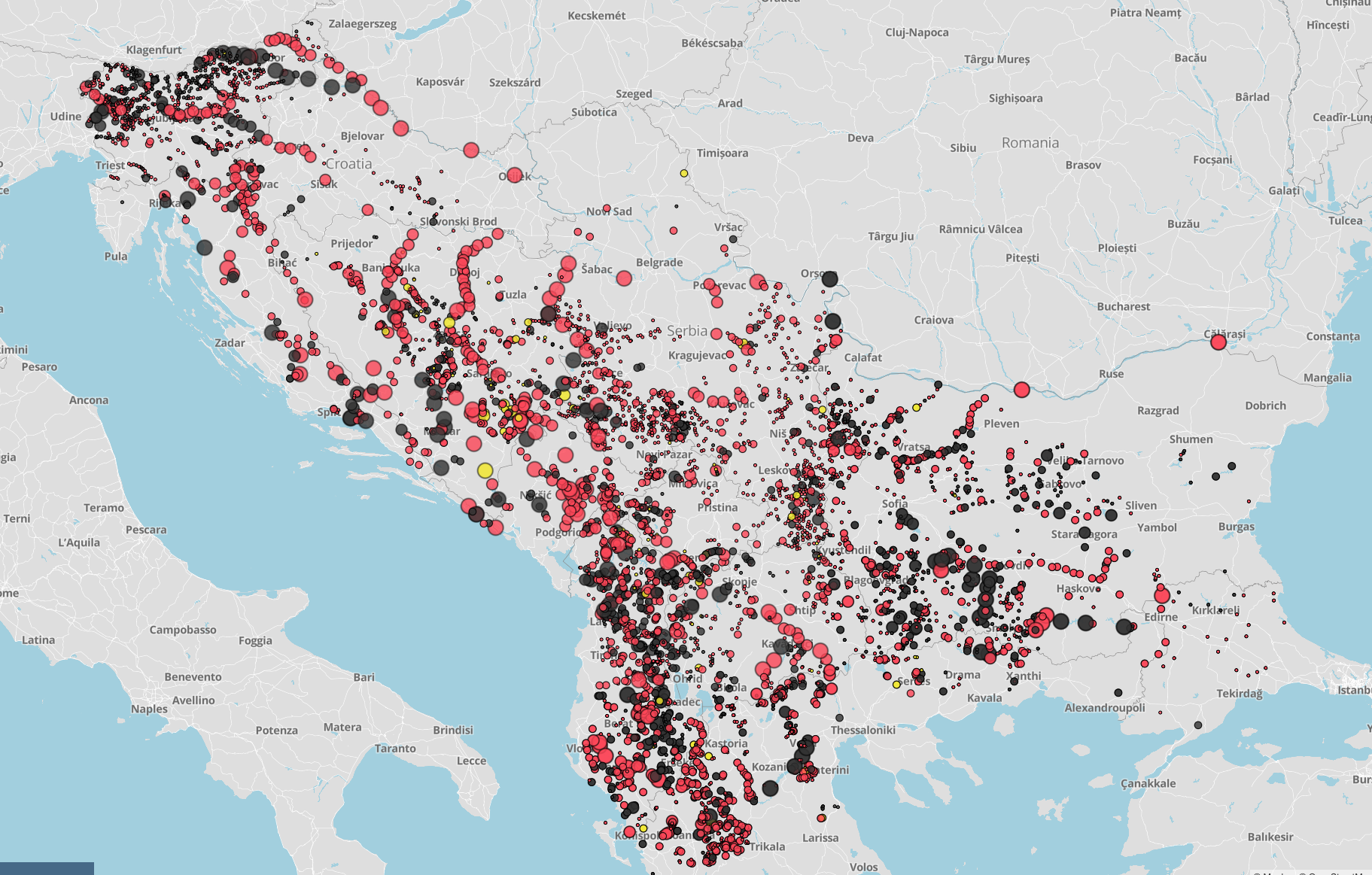

European Union Renewable Energy Goals: The False Promise of Hydropower and the Rights of Rivers in the Balkans

Since the entrance of the Balkans into the EU Energy Community in 2006, the EU has propelled nationalized incentives that have led to an incredible expansion of small hydroelectric power into the Balkans, and this birth of hydropower in the so-called “Blue Heart of Europe” has done immeasurable damage to some of the region’s last intact riparian ecosystems.

Spanish Lagoon Mar Menor Faces Initial Court Involvement and Constitutional Challenges to Its Rights

Spain’s Mar Menor, the first ecosystem in Europe to receive legal personhood, has become involved in several court cases and faces challenges to the constitutionality of its standing.

Whale Personhood in Polynesia

In March 2024, Indigenous leaders from across Polynesia including Aotearoa (New Zealand), Tonga, Tahiti, Hawai’i, and the Cook Islands signed He Whakaputanga Moana (Declaration for the Ocean), recognizing whales as legal persons with inherent rights. Whale populations have suffered significant decline globally due to human activities. Whilst not a binding international treaty, the Polynesian call to grant personhood to whales is sparking conversations around utilizing Indigenous knowledge to protect whales and combat anthropogenic climate change.

The Marañón River Case, Ríos Protegidos Intiative, Native Stingless Bee Project, and More: Six Months in Action with the ELC Latin America Legal Team

ELC’s Latin America Legal Program has developed 4 pillars of our work: 1) Environmental justice initiatives, 2) Nature defenders and human rights initiatives , 3) Legislative and policy initiatives, 4) Global advocacy and movement building initiatives. Together with our partners, we currently have active projects in 5 countries in South and Central America. We have shared our expert insights in more than 20 environmental lawsuits, contributed to the formulation of 15 environmental bills, and successfully passed 4 laws recognizing the Rights of Nature.

Rights of Nature and Ecocide: A Literature Review

Most authors to date view ecocide as a helpful extension of Rights of Nature theory into criminal law. Of course, there would be limitations in the ICC’s enforcement against ecocide, but the move to include ecocide as an international crime against peace nonetheless advances the global narrative on the Rights of Nature. Already, laws against ecocide in France, Belgium, and other countries around the world provide deeply imperfect but useful frameworks for implementing ecocide into national and international law.

ELC Helps Train Nile River Basin Journalists on the Rights of Nature

in the spring of 2024, Earth Law Center (ELC) entered into a year-long collaboration with water journalists from the InfoNile program, including a five-day online training program for Nile River journalists, which was held March 18-21st, 2024, in conjunction with World Water Day (March 22nd), and which focused on the Legal Personhood of the Nile River. Based on the strength of InfoNile’s journalist network and background in training journalists in water, environmental, and science and data journalism, 20 journalists from 11 countries along the Nile River were selected to enroll in the journalists’ certification training on Legal Personhood of the Nile River, with the goal of reporting impactful stories on the Rights of Nature.

The Rights of Future Generations and the Summit for the Future

In this blog post, we break down key terms and concepts related to rights of future generations, Summit of the Future, and Pact for the Future. We also explore the actions of countries with established protection and representation of the rights of future generations and share our suggestions on language for the Pact for the Future.

Nine Important Results from the Escazú COP3

Progress updates on implementation of the Escazú Agreement, which is the first international treaty in history to enshrine rights for those considered defenders of Nature, in order to reinforce the protection of human rights in environmental matters. Likewise, it promotes the implementation of management and governance mechanisms in environmental matters, involving vulnerable groups such as youth, women, and Indigenous peoples in the process.

Re-envisioning Riverscapes and Urban Riverfronts in India: Toward Ecological and Social Harmony

As India undergoes rapid urbanization and experiences a surge in urban population, the issue of urban water security, intertwined with impacts of climate change, looms larger than ever. Amidst these pressing needs, a concerning trend to “develop” and “beautify” riverfronts in urban areas has emerged. The misallocation of public funds for such projects neglects alternative approaches such as Rights of Nature governance for river restoration and rejuvenation initiatives, which would better serve environmental conservation and community interests.

ELC Latin America Team to Cohost Official Side Event at Escazú Agreement COP 3 (Zoom webinar registration link below)

ELC Latin America Team to Cohost Official Side Event at Escazú Agreement COP 3 (Zoom webinar; registration link below)

Rights of Nature or Wrongs to Nature? The Denial of Legal Personhood to Nature in the UK

Defra’s “firm position” that rights cannot be given to Nature falsely conceives of the law as a static entity bound by predetermined “fundamental principles.” On the contrary, the UK’s uncodified constitution gives lawmakers a great deal of flexibility to enact statutes that reflect the evolving understanding of who or what has intrinsic value and deserves rights.

The Global Plastics Treaty and "Plastics Justice"—A Primer

Led by Ocean Program Director Rachel Bustamante, Earth Law Center (ELC) recently released a report entitled “Advancing Ocean Justice in the Global Plastics Treaty.” You can find more information, including links to the full report and a related press release, on ELC’s Ocean Plastics webpage. In this blog post, we break down some key terms and concepts related to plastic pollution, the Global Plastics Treaty, and plastics justice, ending with ways that anyone can get involved in this critically important issue.