Earth Law Center Blog

Welcome to the Wonderful World of Earth Law

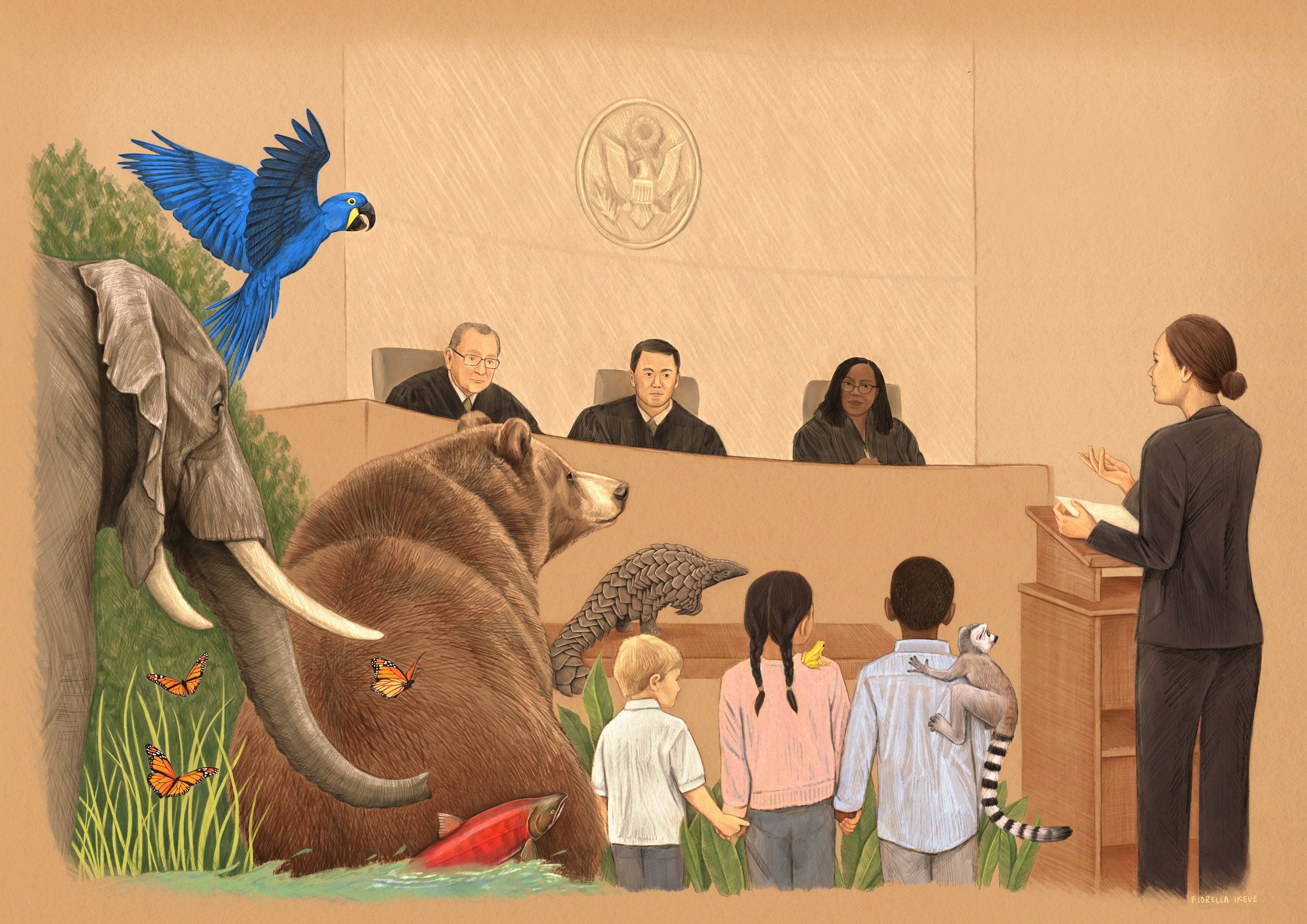

Earth law is the emerging body of law that will protect, stabilize, and restore the functional interdependence of Earth's life and life-support systems at the local, bioregional, and global levels. Earth law may be expressed in constitutional, statutory, common law, and customary law, as well as in treaties and other agreements both public and private.

It’s Time for an Earth Law Textbook

First law textbook on legal movement to establish rights for nature from Earth Law Center. The textbook will be available for university courses and elsewhere. The goal is to train the next generation of rights of nature experts.

Earth Law Clubs at American Universities: Standing on the Shoulders of Giants

Student activism captures media attention, prompting the public to respond to causes. It can shift the paradigm on climate change and policies that are detrimental to the environment.