Ecocide and the Importance of Prevention

Guest blog by Ben Thomas

In this time of crisis and uncertainty, I’ve found some solace in a little morning routine I’ve made for myself. Once I’m out of bed, I have a coffee and glue my eyes to the TV as I wait for Andrew Cuomo, the governor of my home state of New York, to make his morning address on the state of the coronavirus pandemic. While there is evidence that the outbreak of cases in New York could have been minimized with swifter action, the strict measures later imposed have put the state in a favorable position compared to other parts of the country. With the number of new cases appearing to be declining, the governor claims that evidence-based policies will now be critical in order to keep the virus at bay. This includes actions like contract tracing and the systematic reopening of businesses, but I am aware that the rate of Covid-19 cases could easily spike again in New York, as it has in other states. Now that we are a few months into the pandemic, this game of chess between the government and the virus has shed light on a crucial lesson: that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

While many governments around the world were quick to implement reactionary policies to contain the outbreak, some researchers were already spreading the message of prevention, speaking out about what factors ignite epidemics. Many diseases like Ebola, HIV, and now Covid-19 have a history of spreading to humans from wildlife, and studies show that the number and frequency of zoonotic disease outbreaks has been increasing over recent decades. This flood of new diseases is already proving to be one of the 21st century's greatest threats towards humanity, and a new understanding is forming about how human activity has increased our exposure to the viruses and pathogens at the center of it all.

“We cut the trees; we kill the animals or cage them and send them to markets. We disrupt ecosystems, and we shake viruses loose from their natural hosts. When that happens, they need a new host. Often, we are it.” wrote David Quammen, author of Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic, in a New York Times article.

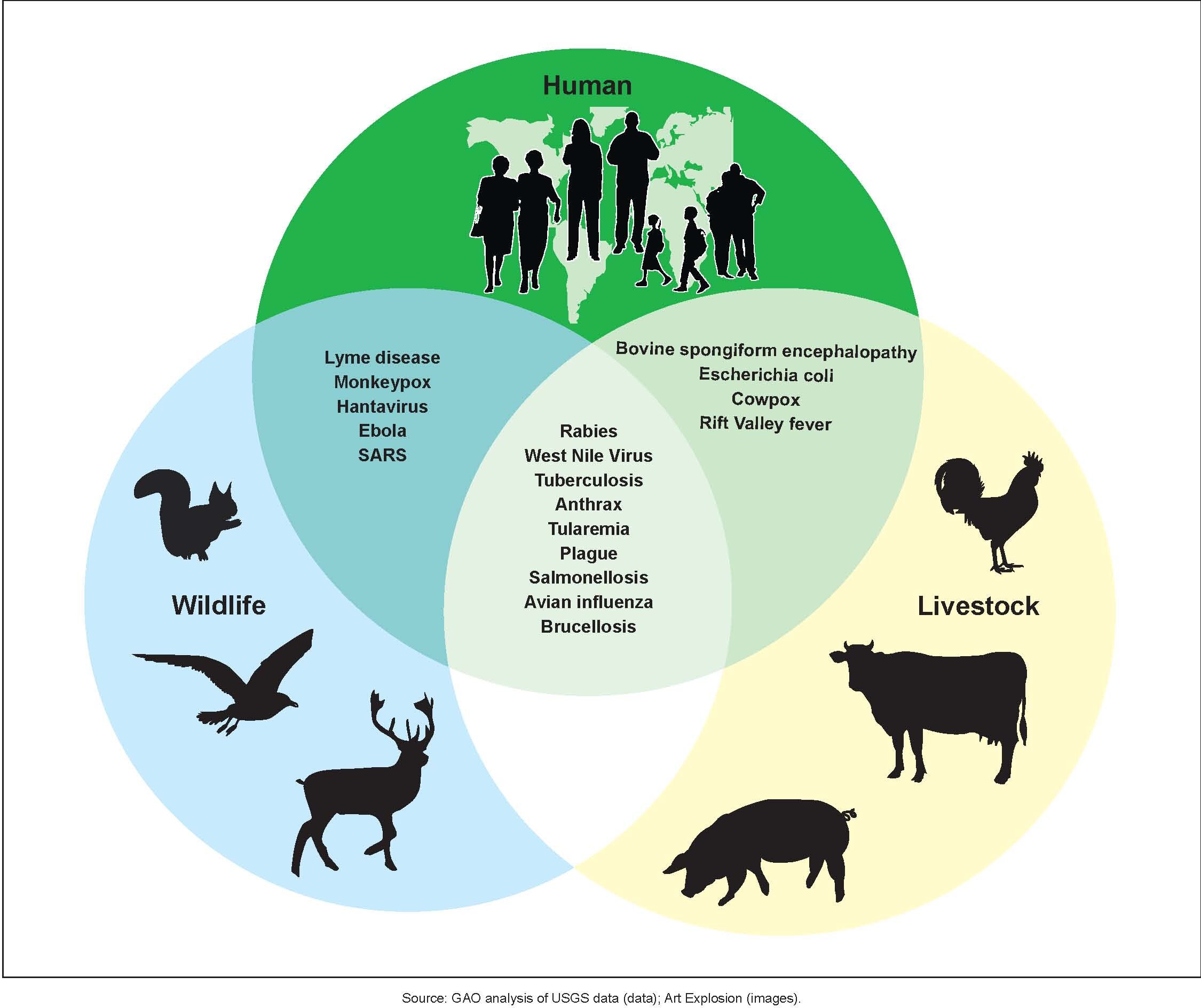

“Possibilities for zoonotic disease transmissions.” Image from U.S. Government Accountability Office from Washington, DC, United States. Licensed under Public domain

Research shows that the rise of many diseases is linked to environmental change and human behavior. As environmental degradation occurs on a larger scale, we become more exposed to wildlife, increasing the likelihood that an infectious disease will make the transition from animals to humans. For example, take this recent Stanford University study that focused on deforestation in Uganda. Combining satellite imagery and in-person surveys, researchers analyzed the factors that led to physical interactions between humans and wild primates in different areas of the country. What they found was quite interesting: It wasn't the large areas of forest with dense primate populations that saw the most interactions, but small patches of forest that were bordered by human populations.

Widespread environmental degradation is already a topic of international concern. For example, the deforestation ravaging the Amazon Rainforest in Brazil has gotten significant media attention. In the Amazon, an area the size of a soccer field is cleared out every minute, and as more forest is converted to farmland, human-caused fires have increased in size and frequency. Last year, deforestation in the Amazon during the first 8 months of 2019 rose 76% above the rate in 2018, the highest overall in a decade, and this led to larger and more uncontrollable fires. As the fires raged, the Amazon began receiving serious international attention.

Millions of dollars were pledged to fight the fires, some countries froze aid to the region to pressure the government to act, and French President Emmanuel Macron even threatened to end a trade deal with Brazil. The private sector also rallied behind the cause. Companies called for a reduction in the reliance on deforestation, and many boycotted Brazilian industries.

It is crucial to make sure that the international response is effective and carefully targets those actually responsible for harm. Economically starving a population of people in response to the actions of their government will not get to the root of the problem. The Brazilian people, especially indigenous communities, remain the greatest victim of the deforestation of the Amazon. Meanwhile, members of Brazil’s leadership and wealthy corporations (including those based in the U.S.) encourage and benefit from the rainforest’s exploitation and deforestation.

Cases like the Amazon’s display the importance of developing a global legal framework in the name of preventing nature’s destruction. If the international community can come together to combat deforestation, why has it been so difficult to get preventative policies on the books?

“Fires and Deforestation on the Amazon Frontier.” Image by Jesse Allen and Robert Simmon. Licensed under Public domain.

Enter Ecocide

Ecocide has a few varying definitions, but all cases refer to the widespread destruction of nature and ecosystems such as which occurred in the Amazon in 2019. Like genocide, ecocide is of international concern, not only because of the aforementioned public health implications, but because without preventative laws put in place these catastrophic events will continue to put our planet and the life that lives on it at risk.

The greatest champion of establishing a set of international laws against ecocide is the late Polly Higgins, who notably claimed that “Ecocide is the missing international crime of our time.” While the few countries that have existing ecocide laws mostly base the crime off a requirement of criminal intent, Higgins argues that ecocide should be a strict liability crime. Under this standard, a person or entity that committed ecocide would be responsible for the consequences of the crime, regardless of the intent behind the action. On top of increasing the effectiveness of enforcement measures, the existence of strict liability would also place the main focus of policy on prevention.

International criminal laws against ecocide actually exist, but they relegate it to times of war. The Rome Statute, the major legal instrument in international criminal law, refers to the act as “widespread, long-term and severe damage to the natural environment…” This falls under War Crimes, one of the four crimes under the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court. Polly Higgins sought to make ecocide the fifth crime under their jurisdiction, establishing it beyond just the scope of military acts. In 2010, she submitted a draft amendment of the Rome Statute to the United Nations. Her definition of the crime of Ecocide is below:

“Ecocide is the extensive damage to, destruction of or loss of ecosystem(s) of a given territory, whether by human agency or by other causes, to such an extent that peaceful enjoyment by the inhabitants of that territory has been or will be severely diminished.”

Since Higgins death in 2019, her work has been carried on by her Stop Ecocide campaign co-founder Jojo Mehta. Jojo and the Stop Ecocide campaign are currently at the forefront of the ecocide legal movement, furthering efforts to get ecocide recognized as a crime in international criminal law.

Artist interpretation of ecocide. Image by Marek Studzinski from Pixabay.

Problems with Enforcing Ecocide

It has been historically difficult to prosecute environmental crimes of this scale, especially when those thought to be responsible are nation states or corporate entities. One reason concerns the process of identifying the victim, which in many cases is nature itself. Nature is generally not considered a holder of legally protected rights, and international statutes tend to limit the definition of a victim to humans.

Finding a responsible party to connect to the crime of ecocide can be even more difficult. Let’s return to the 2019 fires in the Brazilian Amazon. In this case, who were the actors at fault? Was it Brazil’s President, Jair Bolsonaro, who slashed enforcement measures, encouraged development, and eventually declared that the deforestation would never stop? What about the companies that incentivize the fires, creating the demand that finances the deforestation in the region? Lastly, it was individuals that ultimately carried out the burning. Whether a farmer trying to feed their family or an agent acting on behalf of a larger organization, are they any more responsible than the aforementioned parties?

It is important to note that in a global economy where wealthy countries exploit the land and labor of poorer countries, holding the responsible actors accountable can be difficult when they are far removed from the scene of the crime.

The way ecocide is framed can also pose as a challenge to its application as a crime. This is because, in many cases, the act is an externality of another. During a war, some might view destroying nature as necessary to defeating the enemy. During peace, pollution of a river could be considered a negative side effect of increasing manufacturing production. These are both examples of nature being thought of as something for human use. If, as with genocide, the goal of regulating ecocide is to prevent it as much as possible, a new legal framework, one that goes beyond existing environmental laws and paves the way for efficient enforcement, will be necessary.

Conclusion

A discussion I have heard come up a lot regarding the coronavirus outbreak is how to balance the cost to public health with the cost to the economy. It seems the major consensus is that life must be prioritized above all else, and we as a society will deal with the economic fallout after we solve the public health crisis. Furthermore, an economic system can’t thrive when the public is unhealthy and its future is uncertain.

Earth Law takes a similar approach to the ecocide challenge. Under Earth Law, economic benefits to humans are never prioritized over an ecosystem’s right to thrive and survive. The establishment of ecocide finds a nice place within Earth Law, as an ecological consciousness is assumed, and harm to nature is not simply an externality of reaping economic benefits for humans.

Just as this current crisis has brought about changes in the ways through which we empower our communities, we can also change with ways through which we empower the natural world. An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.