How Earth Law Can Help Protect Old Growth Forests

Figure 1 Photo by Mali Maeder from Pexels

By Hali Stuck

Living in West Virginia, nature is a huge part of my life. With a forest as my backyard, I hike weekly. My beautiful and biologically diverse state is in good company. The United States has 154 protected areas known as National Forests, which represent 14% of the total land area of the nation and one tenth of the protected land area of the world. Although this is down from the roughly 50% of forested land that existed prior to the arrival of Europeans, the majority of deforestation took place prior to 1910.

Forests face such destructive threats around the world that the first ever UN Strategic Plan for Forests was created in 2017 at a Special Session of the UN Forum on Forests. The plan has a focus on sustainably managing all types of forests and trees outside forests and on halting deforestation and forest degradation.

Forests cover nearly 30% of the world’s landmass and 18 million acres are lost each year – an area the size of Panama (or between the sizes of South Carolina and West Virginia). At this rate, the world’s forests will disappear in about 250 years – just nine generations away. The United States of America has been a nation longer than that and we are still considered a young country.

So, what can we do about this and why should we care?

What Trees Do for Our Earth

New research has revealed a multitude of ways in which forests create rain and cool local climates. The paper calls for a paradigm shift in the way the international community views forests and trees, from a carbon-centric model to one that recognizes their importance in cross-continental water cycles. Specifically the paper concludes that integrating forest effects on energy balance, the water cycle and climate into policy actions is key for the successful pursuit of adaptation and forest carbon-related mitigation goals.

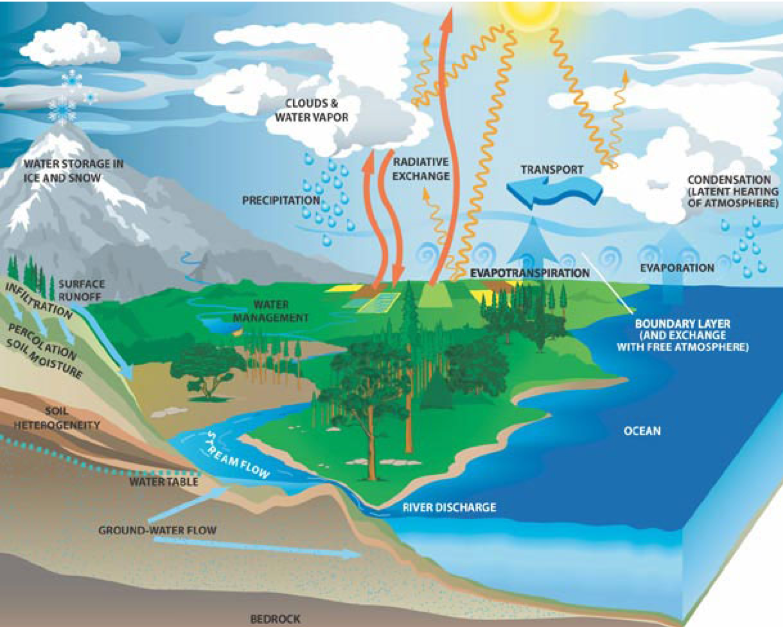

The Water Cycle

Figure 2 Water Cycle. Sagar Purnima

Among plants, trees are by far the most effective evapo-transpirers, adding moisture to the air. Transpiration is the process by which moisture is carried through plants from roots to small pores on the underside of leaves, where it changes to vapor and is released to the atmosphere. Transpiration is essentially evaporation of water from plant leaves.

One tree sends between 250 to 400 gallons of water a day into the atmosphere. Recent studies have shown that as much as 70 percent of the atmospheric moisture generated over land areas comes from plants (as opposed to evaporation from lakes or rivers) – much more than previously thought. New research has revealed that forests also play a key role in water vapor actually forming clouds and then falling as rain.

Trees emit aerosols that contain tiny biological particles – fungal spores, pollen, microorganisms and general biological debris – that are swept up into the atmosphere. Rain can only fall when atmospheric water condensates into droplets, and these tiny particles make that easier by providing surfaces for the water to condense onto.

Local water availability

Research conducted by Ulrik Ilstedt from the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, one of the study’s co-authors, has shown that in dry landscapes, trees (at some densities) can actually increase the availability of water, by assisting with groundwater recharge.

Tree roots – and the animals they attract like ants, termites and worms – help to create holes in the soil for the water to flow through.

Figure 3 Photo by Jeremy Bishop on Unsplash

Forests cool locally and globally

Forests cool the Earth’s surface not just with shade, but the water they transpire cools the air nearby. “One single tree is equivalent to two air conditioners, and can reduce the temperature by up to 2 degrees,” says study author Daniel Murdiyarso, from CIFOR.

Maintaining tree cover can therefore reduce high temperatures and buffer some of the extremes likely to arise with climate change, the authors say.

The Carbon Cycle

Forests contain three-fourths of the earth’s plant biomass, about half of which is carbon. Thus forests play a key role in the global carbon cycle by capturing, storing, and cycling carbon.

How do they do this? Trees absorb carbon from the atmosphere in the form of carbon dioxide, using it as food while producing oxygen as a by-product of photosynthesis. U.S. forests alone store 14 percent of all annual carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from the national economy.

NASA has just released a new map which shows the carbon stored in the forests around the world. Forests in the 75 tropical countries studied contained 247 billion tons of carbon. Consider that 10 billion tons of carbon gets released annually from combined fossil fuel burning and land use changes.

Researchers also found that forests in Latin America hold 49 percent of the carbon in the world's tropical forests. For example, Brazil's carbon stock alone, at 61 billion tons, almost equals all of the carbon stock in sub-Saharan Africa, at 62 billion tons.

Homes

80% of land-dwelling animals live in forests. Even dolphins can be found in rainforests (in the rivers).

Over two-thirds of the species currently listed under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) live in forests. That’s about 4,600 plant and animal species, including the Louisiana black bear, key deer, and red-cockaded woodpecker.

Figure 4 Red-cockaded Woodpecker in Louisiana. Dominic Sherony

Pollution, storm and drought mitigation

One large tree can lift up to 100 gallons of water out of the ground and discharge it into the air in a day. That means trees also absorb rain runoff (which often happens to be polluted) thus preventing some of it from running into streams, rivers, lakes, and the ocean.

Forests can retain excess rainwater, prevent extreme run-offs and reduce the damage from flooding. They can also help mitigate the effects of droughts. Trees have the ability to provide shade and even water to nearby areas. Trees also assist in reducing water pollution by absorbing water before it travels to polluted areas and disperses into nearby streams, lakes, and rivers.

Results of deforestation

Deforestation means “ the permanent removal of standing forests through deliberate, natural, or accidental means.”

Short-term human needs sacrifice long term sustainability when it comes to cutting down trees. Driven largely by the need for: fuel, housing development, timber harvesting for furniture and paper products, clearing land for agriculture and cattle ranching – deforestation has many unintended consequences.

Increased destruction from natural disasters

When rivers cannot cope with rainfall, floods occur. Floods caused an estimated $8bn of losses around the world in the month of March 2019. Human factors contributing to the increased rate of flooding include structural failures of dams and levees, altered drainage, and land-cover alterations (such as pavement) not to mention higher intensity storms and unusual precipitation patterns from climate change.

Rivers that have been dredged and canalized to protect farmland not only destroy riparian ecosystems but also bring flood waters further inland. By re-connecting brooks, streams and rivers to floodplains, former meanders and other natural storage areas, and enhancing the quality and capacity of wetlands, river restoration increases natural storage capacity and reduces flood risk.

50 years ago, the Puyallup River (near Tacoma) endured significant straightening and levee building while opening up the river’s floodplains for people to cultivate and build on. Starting in 2015, the levees on the Puyallup River are being intentionally breached or setback to reconnect the river with its floodplains. Regional efforts resulted in the Floodplains by Design program, a partnership with Washington State’s Department of Ecology, the Puget Sound Partnership, and The Nature Conservancy. Floodplains by Design uses a competitive process to fund multi-benefit floodplain restoration projects that “improve flood protection for towns and farms, restore salmon habitats, improve water quality, and enhance outdoor recreation”.

Figure 5 Map of the Puyallup River.

Climate Change

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is an important heat-trapping (greenhouse) gas, which is released through human activities such as deforestation and burning fossil fuels, accounting for 82.2% of all US greenhouse gases.

Deforestation not only removes a key absorber of carbon dioxide, felled trees also release back into the atmosphere all the carbon they’ve stored. Burning or leaving trees to rot causes further emissions – with deforestation responsible for about 10 percent of worldwide emissions.

Scientific American notes that deforestation in tropical rainforests adds more carbon dioxide to the atmosphere than the sum total of cars and trucks on the world’s roads. According to the World Carfree Network (WCN), cars and trucks account for about 14 percent of global carbon emissions, while most analysts attribute upwards of 15 percent to deforestation.

Figure 6 Rainforest loss over time.

Disease and species loss

Due to the clearing of the forests, animals have to either compact themselves into smaller environments or move into closer proximity to humans resulting in an increase in zoonotic diseases (a disease that normally exists in animals but that can infect humans).

According to EcoHealth Alliance 31% of new outbreaks of Nipah virus, Zika, and Ebola have links to deforestation.

They also say that areas that have experienced significant amounts of deforestation are more likely to see an Ebola outbreak in two years than an area that has not.

What has been done

In 2016 the Paris agreement became available to signatures from within the United Nations. The agreement aims to prevent global temperature change from reaching the 2 degrees threshold. Signatories agree to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by switching to greener and more stable and effective technology.

Currently the only country that has not signed is the United States.

Other acts such as the Wilderness Act and the Lacey Act help to prevent deforestation by outlawing imports of illegal wood.

Figure 7. Forest in Inverness, Reino Unido. Photo by Luis Del Río Camacho on Unsplash

How Earth Law can help

Rights of Nature can help protect forests by recognizing the inherent rights of forests to exist, thrive and evolve. The needs of a forest ecosystem can be considered along with the needs of other parties, so that win win solutions can be created instead of ones that only result in the destruction of forest ecosystems.

Forest rights are currently at the forefront of Earth Law Center’s work, partnering with Eneas Wilfredo Martínez Santos and other partners in El Salvador to draft a Declaration of the Rights of Natural Forests in El Salvador.

Earth Law Center supports the idea that humans have a responsibility for how we impact the world around us. The belief that nature — the species and ecosystems that comprise our world — has inherent rights has proven to be a galvanizing idea, and we work with local communities to help them organize around the rights of nature to protect their environment from the threats that they see.

The heart of the ELC approach is to seek legal personhood for ecosystems and species, a designation similar to that given to corporations in U.S. law, and one that if done well will imply both rights for the entities so designated and responsibilities on the part of human beings and societies to respect those rights.

Empowering nature empowers communities: when advocates see themselves as rights defenders rather than responsible stewards of nature for human ends, the stakes are raised, and the relationships between people and the environment is transformed. ELC connects these emerging local advocates to build regional movements, with the ultimate aim of creating national and international momentum for a radical change in how humans view and interact with the natural world.

Here’s more you can do: